The Thaumaturge exists in an alternate 1905 Warsaw, where I can’t go anywhere without a couple of soldiers trying to mug me for my nice warm boots, and making matters worse, I’m playing an exhausted-looking guy who keeps talking to himself. This RPG world doesn’t have the same immediate appeal as a fantasy realm like Baldur’s Gate 3’s Faerun, but once I start digging, I find a treasure trove of great writing and compelling choices.

The game starts with a short tutorial that introduces us to Wiktor Szulski, our prideful protagonist. Wiktor is a Thaumaturge, a mage who invokes ancient rites to bind spectral entities and cryptids known as salutors to his will. He’s also kind of an asshole; the only people he’s even close to are his beloved sister and his new pal Rasputin. (Yes, that Rasputin.) While the tutorial takes place in a small village, allowing the player to figure out Wiktor’s skills in a low-pressure environment, before long I’m headed to Warsaw to investigate a mystery with much bigger stakes.

Whenever a game throws a bunch of proper nouns and mechanics at me, there’s always the risk that I miss something. Thankfully, Fool’s Theory, the developer of The Thaumaturge, does a good job of introducing concepts naturally. This is the kind of game I was able to blitz through in a few long sessions because I was always eager to talk to one more person, find one more conclusion, solve one more quest.

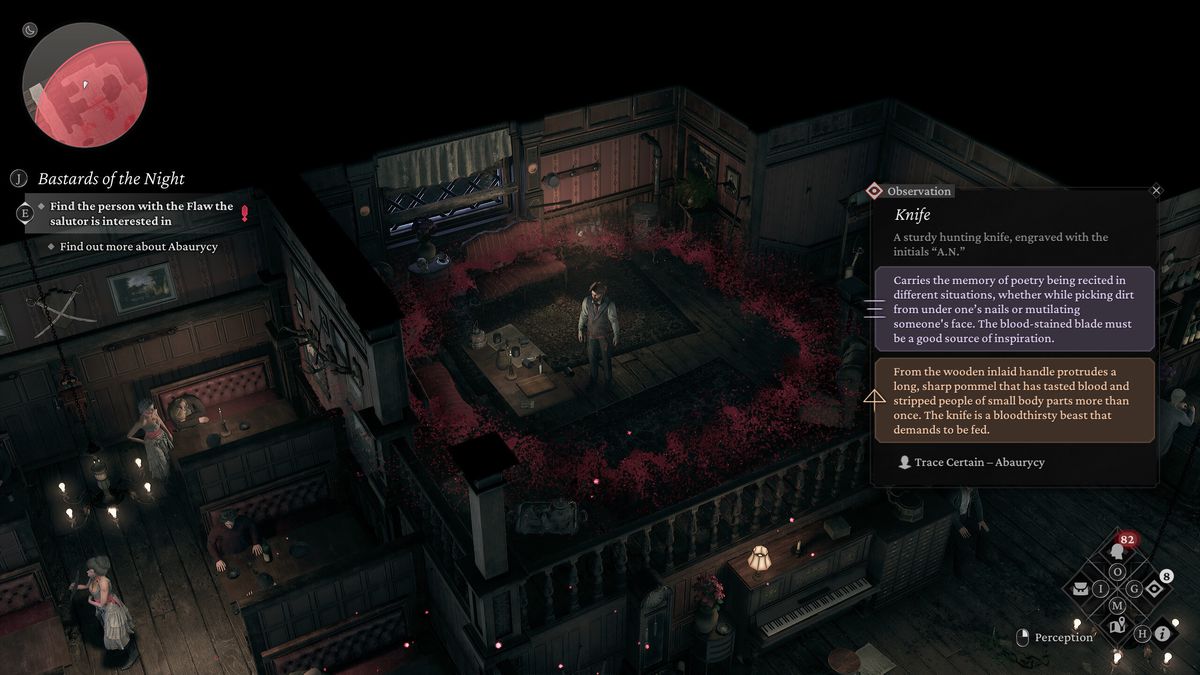

Using Wiktor’s Thaumaturge powers makes up a big part of the game. Certain items leave a Trace, a marker of its owner and a big way to find evidence throughout the story. For instance, during the tutorial, I found a year-old bloodstain smeared on a scorched floor. Simply taking a gander at it is enough to tell me how the person died, the murder weapon, and their emotional state at the time. It’s important that I track these mysteries, too, because in this universe, bad vibes are more than simply an unpleasant experience — they’re downright deadly. Major moral flaws draw in salutors, who then menace the populace.

The closest comparison I can draw here is with the Witcher universe, another paranormal Polish franchise. Both depict mundane life, with people worried about “normal” concerns like war, economics, and their families, but they also happen to live side by side with monsters and magic. At one point, I have to solve the mystery of why everyone in an inn has gone murderously mad. Sure enough, after a little digging, I find an evil phantom. Geralt and Wiktor could probably get drinks and kvetch about the monster hunting biz.

In this universe, Thaumaturges need to bind one salutor to their will to keep them grounded. However, Wiktor’s a little more ambitious than your average Thaumaturge; much like a haggard Ash Ketchum, he wants to catch them all. I eventually end up with half a dozen in my command, and they are visually striking. I start with the Upyr, a demonic creature from Slavic mythology who looks like a floating skeleton wrapped in heavy furs and that drains an enemy’s health and heals Wiktor. My enemies can’t see him, but I get a kick out of watching him hover behind my enemies with his pitted sword.

Here’s where The Thaumaturge opens up to be more like a traditional RPG, with a combat style reminiscent of the Yakuza games. Wiktor starts out brawling with his fists, and I can either choose a quick attack or slower but more powerful hits. As I bind more salutors to my will, I can switch them into battle. The Lelek is a weird little bird-thing that inflicts insanity and chaos on my opponents, while the Bukavac is a great chained bone-beast that inflicts stacking damage effects on my foes.

But while Wiktor is a Thaumaturge, he can’t solve every problem with magic or salutors. He also must serve as a detective. If I find all the evidence I need, I can draw conclusions, which open up new conversation options. I can blunder through situations with blunt force, but if I want the cleanest possible solution, I have to look around. Certain discoveries are locked behind Thaumaturge schools, which I can only unlock through leveling up. There are always choices to be made, and most of them have some kind of drawback.

This is especially true when it comes to Wiktor himself. He has a “flaw,” a failing so large that it risks drawing in salutors and causing all kinds of trouble. He struggles with pride, so I get lots of conversation options marked with the little pride symbol. A lady asks me to kneel and tie her shoe so she can sneak a private conversation in? I can do so like a gentleman, or I can snap at her for treating me like a lackey. Wiktor is very aware of his pride, and he finds that other people have similar flaws — wrath, greed, and so on. All of these can inspire discontent, violence, and the arrival of more salutors to mess with the innocent populace.

The more I indulge in my sin of pride, the more conversation options open up down the line. It’s a balancing act between not wanting to be a doormat and not wanting to lose Wiktor entirely to his curse. It’s especially tough to be a kind and patient person in Warsaw.

The city is a thriving character of its own, a place of contrasts and conflict. There are fliers in the street encouraging the workers to sign up for labor unions and organize for a nine-hour day posted next to warnings of evil Thaumaturges that must be rooted out, lest they bring devils and despair. The city is held by the Russian tsar, but it’s made up of various people. Jewish merchants trade with Polish townspeople who resent the Russian soldiers watching over their shoulders. A seedy underbelly of crime flourishes, while the rich of the city enjoy ballrooms and banquets. Wiktor is an outsider in Warsaw who views the city with contempt. The city, in turn, treats him with suspicion.

The game even opens with an acknowledgment of the real-world issues it’s tackling with its storytelling. It reads:

Fool’s Theory is a team of people with diverse beliefs, religions, sexual orientations, and gender identities. Our goal is to tell mature stories that are meant to be a source of reflection for players. We would like to point out that in creating a game that draws so much inspiration from the past, we could not leave out the portrayal of certain attitudes and views that are rightly considered unacceptable today.

There are times when this writing philosophy is jarring; upon arriving in Warsaw, I’m immediately greeted by an agent of the tsar who rants about the enemies of the state. It’s an ugly sentiment, but one that feels real and is grounded in history, and it immediately motivated me to look beyond Wiktor’s selfish concerns and start helping those under the tsar’s malevolent reign.

There’s the issue of jank, however, which is to be expected from an ambitious game by a smaller studio. At one point, all of my saves were corrupted by an update, which was a bit of a pain in the keister. I even had to restart the game a few times due to memory issues. On a smaller scale, certain cutscenes feel a little rushed and imprecise, with characters clipping through terrain or suffering from awkward animations. It’s never enough to ruin the vibe, but it can be irritating from time to time.

That said, The Thaumaturge manages to do a deft job weaving between its supernatural story and the context of its historical setting. Wiktor is an outsider, and his detachment from society means that he can pick a side. I chose to have him back the unions and be a real comrade, but the game has tons of branches — including some where he falls to pride or commits sins that he cannot erase. These are the choices that make The Thaumaturge worth it, even when I’m annoyed by its technical shortcomings. Wiktor’s powers, detective skills, pride, and values are all things that can change the decisions at hand, and when I make a choice, it feels weighty. Since this is an RPG that lasts about 25 hours, I’m already getting amped up to see how a second run changes things. I have the feeling, though, that no matter how hard I try, something is going to go terribly wrong for someone.

The Thaumaturge was released on March 4 on PlayStation 5, Windows PC, and Xbox Series X. The game was reviewed on Windows PC using a pre-release download code provided by 11 bit studios. Vox Media has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content, though Vox Media may earn commissions for products purchased via affiliate links. You can find additional information about Polygon’s ethics policy here.