Trading card games aren’t just popular with players. They’re also incredibly popular with executives, as they can be lucrative for publishers and distributors alike. Magic: The Gathering became a $1 billion brand for Hasbro in 2023, which went quite a long way to improving its bottom line, if we’re being honest. As the company increases its Universes Beyond offerings, incredibly powerful tools for selling cards to people not yet comfortable playing a game of Magic, how can other TCGs hope to compete? What must new games like Disney Lorcana, Star Wars: Unlimited, Altered, and the more established Flesh and Blood do to thrive? A few possible answers may lie in the story of the 1990s-era Dune: Collectible Card Game.

The TCG market in 1997 was not so different from today. Magic: The Gathering reigned supreme. Dozens of competitors and a few blatant cash grabs had all come and gone. Every new game sought either a new gimmick, a popular IP, or another way to offer something Magic did not. Enter the company Last Unicorn Games with Dune: CCG, which asked players to turn the wheels of a galaxy-spanning political machine in the hopes of being admitted to the Landsraad, the main political body of the Dune universe. Dune: CCG was built from the sand up to be a multiplayer game, not unlike Magic’s community-made format of choice, Commander. Rather than always paying a straight cost in mana to play a card from their hand to the table, players could bid against one another to inflate the costs of the choicest cards. To win, players had to accumulate both favor on the political stage and the valuable resource spice from Arrakis. There was even a third resource that helped to further complicate things.

Adding to the cognitive load was the fact that each player brought two different decks to the table. The House deck included most of the cards and types: generic characters, military units, events, etc. Cards in the Imperial deck represented main characters and locations from the Dune story. The cost of these powerful allies and unique locations could be inflated from their base price based on the bidding system, known as petitioning. As the game progressed, players developed their positions, amassed resources, and launched attacks at one another until one player emerged victorious.

If you know Frank Herbert’s Dune, you know that’s pretty spot on. So, while Dune: CCG succeeded in capturing the feel of the universe that inspired it, looking back it’s very much a game from a different time — a time when designers pushed the limits of what could, or perhaps should, fit within the framework laid down by Magic.

But it wasn’t all bad. Let’s look back at the Dune CCG, and four lessons it teaches from which all modern TCGs should learn.

IP alone isn’t enough

Making a Dune CCG meant more than putting Paul Atreides on a card. Its gameplay had to make players feel immersed in the universe of Dune. This meant needing complex political and economic elements, as well as multiple avenues for player interaction. The game succeeded (perhaps too well) in all these goals, with a bidding system for bringing into play the most powerful cards, and four avenues of combat. The multiple avenues of combat and interaction allowed players to pick factions and build decks with characters and other cards fitting their play styles and the Dune universe.

In much the same way Dune: CCG succeeded in being true to its source material, the Star Wars: Unlimited TCG from Fantasy Flight Games does an excellent job making players feel like they’re part of a galaxy far, far away. The game centers around leader cards with powerful abilities representing the larger-than-life characters of the franchise, whom players construct their decks to support. The playing area is divided into two fronts of battle (ground and space) simulating the action of the movies. Whether defending Echo Base with Chewbacca or commanding the Imperial assault from the Death Star with Vader, you’ll agree the Force is strong with this one.

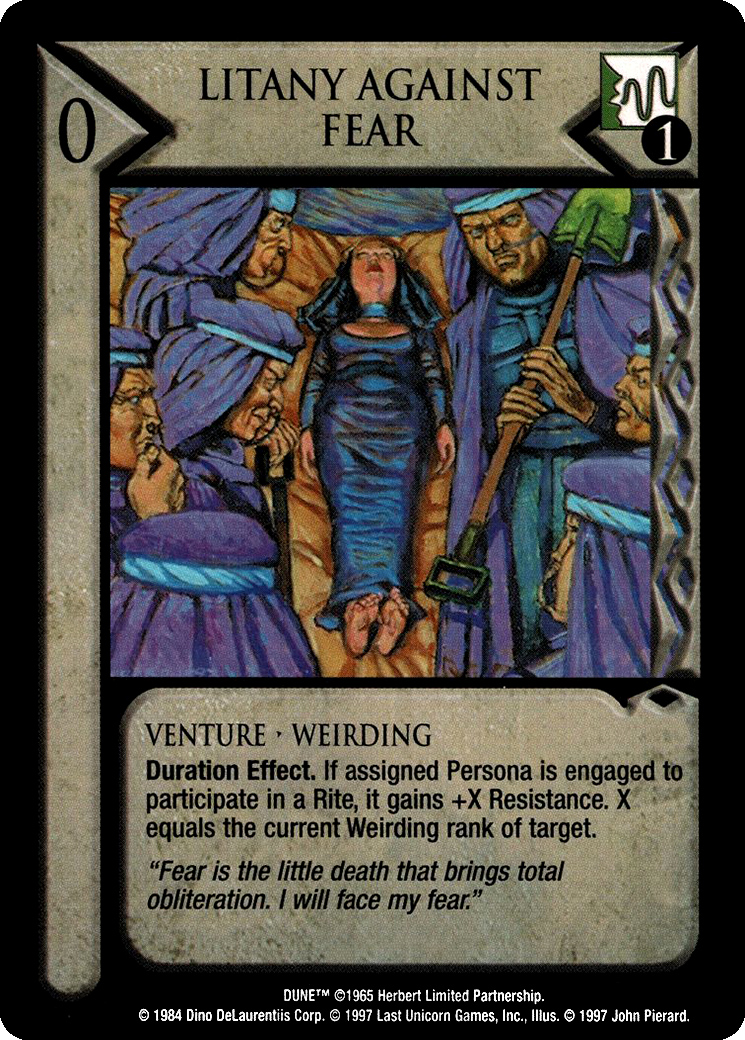

Graphic design is just as important as art

Conveying to players everything they needed to know on the faces of their cards was something many ’90s TCGs struggled with. Art can’t make up for poor graphic design, no matter how beautiful. Dune understood this. The art by Mark Zug and others was brilliant, and the graphic design of the cards conveyed a lot of information in a form that was easy to grok once players were familiar with the numerous symbols, card types, and subtypes — and boy, were there a lot of subtypes — in a style that felt appropriately Dune-like.

Ravensburger’s Disney Lorcana is a modern example of a game that delivers an attractive product in both art and design. If you’ve played any TCGs prior to Lorcana, it’s easy to have a sense of how the game is played just by glancing at the cards. The costs and stats are all highlighted and color-coded, and even indicate which cards may be used as resources.

Encourage interaction

For a game with a lot of moving parts, Dune: CCG had an incredible amount of interaction. The petition mechanic involved all players in the playing of the most powerful cards. As the heart of the game, this made player interaction a fundamental component deeper than most other TCGs. Additionally, players wishing to thwart an opponent’s actions could play Tactics cards at almost any time, much like Instant spells in Magic.

Many TCGs today avoid player interaction at fundamental levels, to the point of eliminating the ability to play cards during another player’s turn or phase. Instead, many games only allow play on a player’s turn, or opt for a back-and-forth action system, limiting players to one action or card play at a time, regardless of their resources. This rigid structure makes games of this fashion easy to learn, but it also makes gameplay feel on rails at times. Thwarting an opponent’s attack or other critical play with a well-timed Instant, Defense Reaction, or Tactic card is what gives games like Magic, Flesh and Blood, and Dune strategic depth other games lack.

Move beyond physical cards

The tangibility of physical trading cards is both a strength and a weakness. If a TCG is popular, it can develop a robust secondary market, making cards readily available. Popularity can also be a double-edged sword. If the game is in short supply, it can lead to resellers snatching up the available product, skyrocketing prices, and strangling availability for players. If prices for singles grow, it can lead to unscrupulous individuals trying to profit by passing off counterfeits. All physical TCGs are subject to these forces, and Dune: CCG was not immune. The brief lifespan and small print run have led to high prices on the secondary market today. This is surprising given the game’s premature death and small following.

Altered is a TCG trying to sidestep the downsides associated with physical cards via proprietary technology. While physical cards will exist in booster packs, what’s more important are the unique QR codes players can scan to establish ownership. Did your chase card get lost or damaged? No worry. You can log into your account and have another copy printed and sent to you on demand. Want to foil your favorite card? Crack a foil code in a booster pack and you can upgrade it. Altered recently wrapped the most successful TCG Kickstarter in history, so the idea certainly has traction. It remains to be seen whether this will revolutionize TCGs or become the tabletop gaming equivalent of the Bored Ape fiasco.

While Dune: CCG was short-lived, it was true to its source material and remains a nuanced game with strategic depth and gameplay worthy of its steep learning curve. For that reason, it maintains a devoted following. The last word on the game might best be expressed by the publishers themselves: “You don’t have to be the Kwisatz Haderach to play, but it helps.”